Does it come as a surprise to you if I tell you that most organizations are lousy at innovation? How else do you explain the fact that some great ideas languish in organizations whereas some poor ideas reach the market? How else do you explain that so many people whine that their organizations do not value their great ideas? Let’s take a look at a well-known example:

How Fat-Free Oil Failed

In 1968, when F. Mattson and R. Volpenhein, two researchers with Procter & Gamble, began working on a cooking fat substitute, they knew they were on to something big. By 1987, P&G had named this substance Olestra and received FDA approval to use it as a fat substitute. Olestra was “the single most important development in the history of the food industry,” according to a Drexel Burnham Lambert stock analysis. What else would you expect from a fat-free oil? The promise was immense – you can gulp down packets of potato chip and not only avoid the guilt but also see no effect on your gut. P&G spent hundreds of millions on setting up the manufacturing facilities for this revolutionary product. In the mid-1990s, the product went to the market. However, by 1997 there were reports of over a thousand adverse reactions from Olestra – from severe diarrhea and fecal incontinence to abdominal cramps. Soon after FDA required that Olestra containing foods have a label warning “Olestra may cause loose stools and abdominal cramping.” In 2002, P&G sold the Olestra plant to Twin Rivers Technology at a substantial loss.

Let’s take another example:

How The Computer Mouse Found A New Home

In 1964, when Bill English, a researcher at Stanford Research Institute (SRI), looked at the hardware design of his new device, he was immensely satisfied to see that it allowed a computer user to move the cursor across the screen by just moving the device with hand. This project led to what was later called the computer mouse. When English moved to Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), he further improved the mouse design and created the ball mouse. Given the ubiquity of mouse for computer users over many decades, one would expect that Xerox would have made a fortune on this product. Unfortunately, it was Apple that made that fortune not Xerox. Apple bought the patent for mouse from SRI for less than $50000 whereas the mouse project at Xerox languished on the sidelines. With the mouse, I am not sure how user friendly the original Apple computer would have been.

Why do some ideas survive in organizations whereas others fail to do so?

The Existential Question of Innovation Effectiveness

Why did PARC not recognize the potential of this idea and why did P&G take a potentially bad idea to the market? What is it that makes companies do this? To understand why this happens, one needs to ask a fundament question: why do some ideas survive in organizations whereas others fail to do so? And when you go down this rabbit hole, you find something interesting.

The Heart of Innovation Problem – Two Funnels

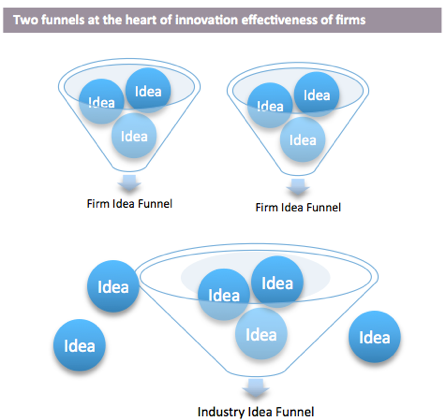

It boils down to a simple fact that organizations are idea funnels, and so are the markets. A market chooses some ideas to become blockbusters and rejects the rest. And the same way, organizations are also environments. They also select a small set of ideas that survive the organization. And then those ideas become a reality and go to the market. And once they are in the market, they compete with a lot of other ideas; some of them survive in the market while others die.

In essence, there are two funnels that you can conceptualize here: an organizational funnel and a market funnel. So how well a job your business does in innovation depends on how well your organizational conduit aligns with the market funnel. Most organizational funnels are

How well is your organizational funnel aligned with your market funnel?

Please note: I reserve the right to delete comments that are offensive, or off-topic. If in doubt, read my Comments Policy.